Amaras Monastery

Hamlet Petrosyan (Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, National Academy of Sciences of Armenia, Yerevan State University)

The Amaras Monastery is one of the complexes that have undergone significant changes over time. Its original church, which existed as early as the 4th century when the remains of saint Grigoris were buried, was no longer present by the end of the 5th century when the relics of the saint were discovered and the reliquary for his relics was built. The above-ground portion of Grigoris’ reliquary was also gradually destroyed over time. In the 17th century, a domed church was constructed on top of its underground section, and in the mid-19th century, the current church was built on the same site. During the 17th and 18th centuries, the existing fortress and economic structures were built and later underwent modifications in the 19th century. As a result, the monastery’s graveyard, along with most of the old monuments, tombstones, and inscriptions, gradually disappeared over time.

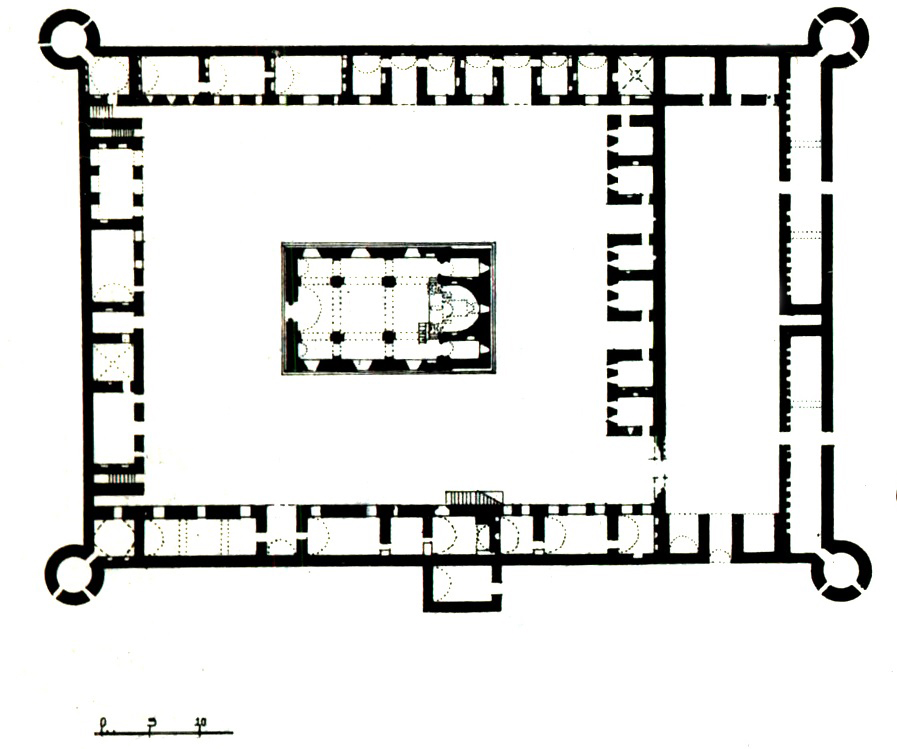

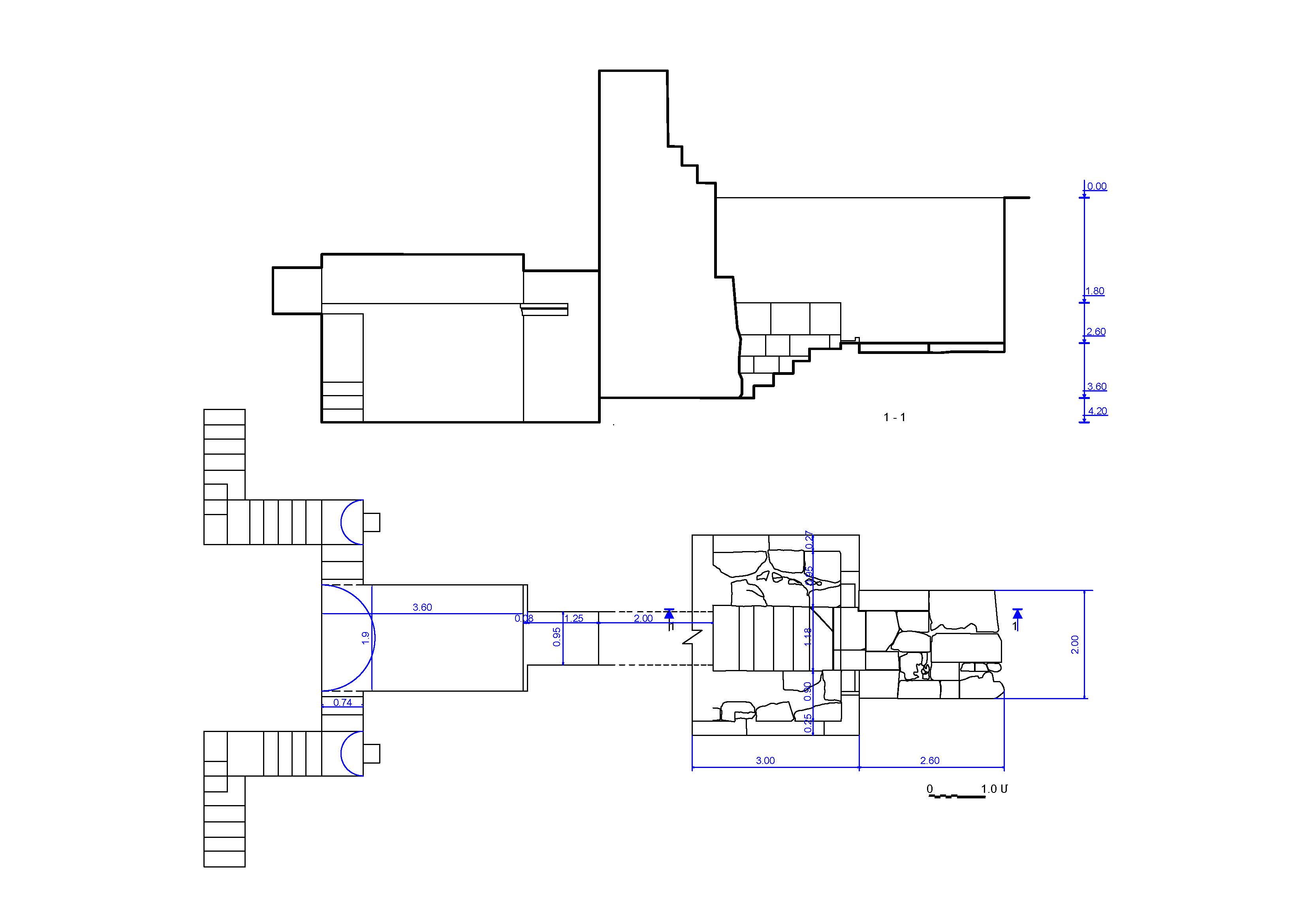

Today monastery complex presented itself as a late mediaeval castle (mainly from 17th century), with defensive walls, towers, living and economic buildings adjusted to the defensive walls in inner part, the church of saint Grigoris bult in 1858 which incorporated the western part of reliquary of saint Grigoris (Fig. 1–2). The reliquary (Fig. 3) was constructed approximately 150 years after the saint’s passing when his relics were discovered and subsequently distributed among various sanctuaries. Recent findings from the 2014 excavations conducted by the Artsakh archaeological expedition in Amaras indicate that it lacked a traditional burial chamber or chapel. In light of the latest research, it is more appropriate to categorize this structure as a reliquary. This monument stands out as the oldest and most prominently dated early Christian architectural and sculptural monument in Artsakh. The main volume of the sepulchre is located under the eastern altar of the present church built in 1858. The sepulchre had two southern and northern entrances, had a long corridor instead of an altar and based on the look of it had been cut during the construction of the church, and the continuation of this corridor should be outside the church behind the eastern wall. The excavations in 2014 revealed the continuation of the corridor with an eastern portal with pavement and six stairs going down and entrance (Fig. 4), quite unusual in the context of traditional church architecture, but which scholars link to the layout of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem. The sculptural reliefs form part of the repertoire of early Christian art: palm trees on the hills (Fig. 5). The sepulchre was partly in the underground and partly on the ground. The fragments of more than one hundred early medieval tiles found during the excavations testify that the roof of the structure was tiled

The central and most prominent building within the expansive western religious courtyard (measuring 46.0 x 59.0 meters) of the Amaras Monastery is the Saint Grigoris Church (Fig. 6). It was constructed in 1858, replacing the previous church that once stood on the same site. The Surb Grigoris Church follows the architectural composition of a nave basilica, featuring two pairs of pilasters, which is characteristic of late medieval Armenian architecture (Fig. 7). The rectangular structure of the church, with external dimensions measuring 13.5 x 23.2 meters, is elevated on a two-level wall base. The church has a single entrance, situated on the western side. The spacious prayer hall, measuring 11.25 x 15.9 meters, is divided into three naves by two pairs of cross-shaped pediments with arches supported by them. Towards the eastern end, the central nave culminates in a tabernacle, flanked by vaulted storage chambers on each side, both having a rectangular layout.

The Amaras complex, which predominantly assumed its current layout in the 17th century, is rectangular in shape, encompassing an area of approximately half a hectare. It is enclosed by walls that reach a height of 5.0 meters. The level terrain facilitated the implementation of a systematic layout for the complex: residential and ancillary structures are constructed within the full extent of the towering, upright walls. Moreover, the eastern section of the complex is demarcated by a series of living quarters, resulting in the formation of two internal courtyards. The eastern courtyard serves primarily for economic purposes, housing the monastery’s barn, stables, and cellars in its vicinity. Meanwhile, at the heart of the larger western courtyard, measuring 46.0 by 59.0 meters, stands the main structure of the complex, the three-nave basilica of St. Grigoris. This courtyard serves as the focal point to which all the monastic chambers open. Additionally, on the southern and western sides of the yard, one can find the refectory (Fig. 8) and the monastery’s two-story building. To safeguard against potential threats during times of political instability, the Amaras Monastery boasts a vital defensive infrastructure in the form of fortified walls equipped with towers. Positioned at each of the four corners of the walls are circular towers, each with a diameter of 6.0 meters. This architectural approach is a recurring feature in the fortifications of various monastic complexes dating from the 17th century in Armenia.

Today, only two khachkars (cross-stones) are known from Amaras Monastery. The inscription on the first khachkar is particularly noteworthy, as it also discloses the names of the khachkar and the artisan responsible for its creation: “Surb Astvatsatsin, in the year 1091 of the Armenian calendar, I, Abraham, the elder priest, constructed this. Remember me in your prayers to the Lord. I, Ghazar, compiled this. Remember me in your prayers to Christ and the Lord” (Fig. 9). It’s worth noting that the Armenian date is exclusively employed in the inscriptions of Artsakh, Utik, and Caucasian Albanian regions. This fact serves as evidence of the calendar unity between the Armenian and Caucasian Albanian churches. The second broken khachkar is dated to 1205 year and presents the feast under the pomegranate tree (Fig. 10).

According to a tradition the inventor of Armenian alphabet Mesrop Mashtots had opened one of the first schools in Amaras. Today walls of the monastery are covered by the Armenian letters in alphabetical order and titled as “Lessons” (Fig 11).

Bibliography

Hasratyan, M., “The architectural complex of Amaras”, Journal of Historical Studies 5 (1975), p. 35–52.

Petrosyan, H.L., “Early Christian Archaeology and Monuments in the Armenian-Azerbaijani Conflict Zone: Tigranakert, Amaras, Vachar”, Armenische Geschichte und deren Spuren in Berg-Karabach, Kiel: Kiel University Publishing, 2024, p. 467–489.